By Max Gulker

By Max Gulker

The U.S. government spends just shy of $1 trillion per year on aid to low-income Americans. This would be enough to give each of the estimated 40 million Americans living in poverty a check for over $20,000 per year. In two previous articles, I showed how the current failed system grew out of a snowballing bureaucracy and misguided paternalism from the left and right.

One can debate the role of government in addressing poverty within society at large. But the short-run imperative to switch the U.S. welfare system to one based on simple cash payments is clear. Much of the discussion along these lines has focused on a proposed universal basic income (UBI), which would provide cash payments to all Americans.

The prospect of a safety net devoid of loopholes and bureaucracy is tantalizing. Unfortunately, fiscal reality reveals UBI to be little more than clever arithmetic and a distraction from more modest changes to welfare policy and the tax code that would directly help those most in need.

Drowning in Trillions

We consider as an example a UBI that would provide all Americans with $1,000 per month, or $12,000 per year (about equal to the individual poverty line). This is the amount proposed by Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, who has billed it as not only a way to address current poverty but to protect working families against potential future joblessness stemming from increased automation in the workplace. I remain agnostic on future technology and focus on what a UBI would mean today.

Providing $12,000 annually to all 325.7 million Americans would cost $3.9 trillion. To put that figure in perspective, the entire 2018 federal budget was $4.1 trillion. Of course, taxpayers could realize some savings if the government eliminated the almost $1 trillion currently spent on aid. At the same time, however, UBI would rain cash on many Americans who simply don’t need it.

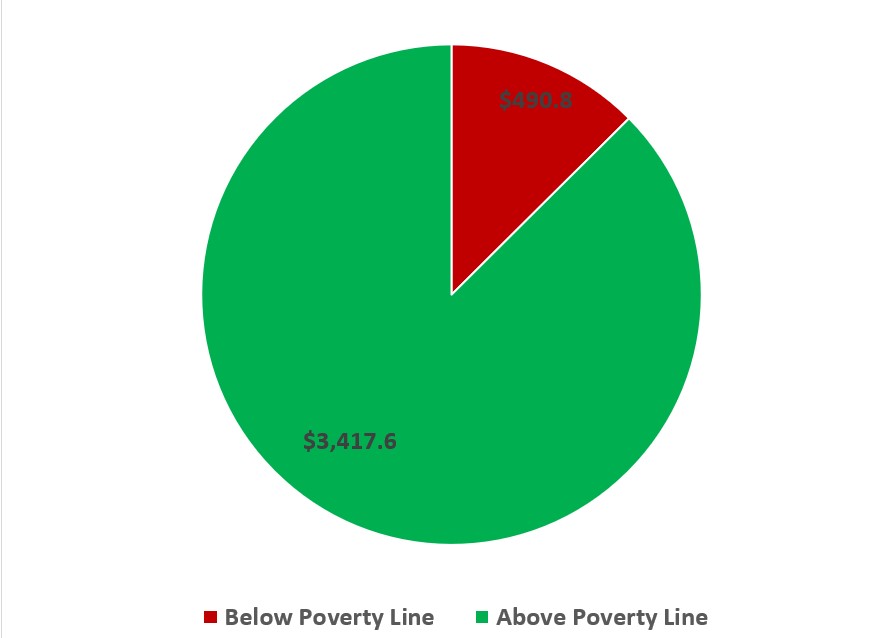

Under $500 billion would go to Americans most needing a basic income, while $3.4 trillion would go to the rest of the population.

Estimated Cash Payments to Americans Below and Above the Poverty Line ($ billions)

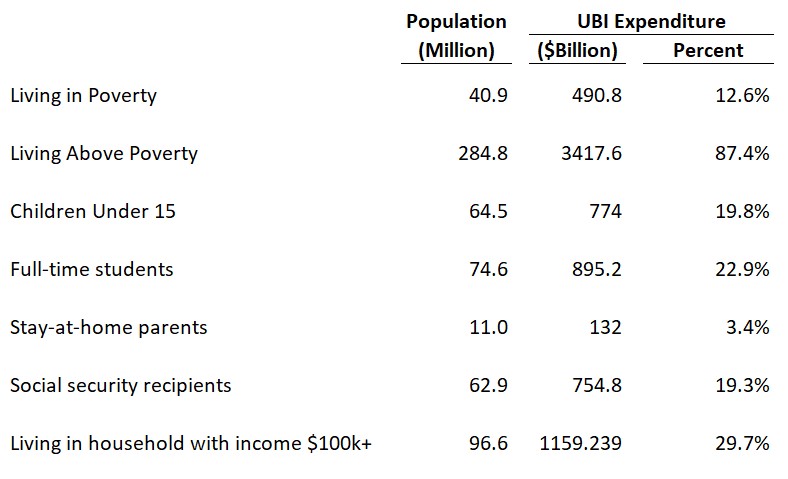

As the table below shows, the $12,000 guaranteed in our example would certainly help many not living in poverty, covering living expenses for full-time students and stay-at-home parents. But the $1.2 trillion handed to the 30 percent of Americans living in households with income greater than $100,000 would amount to nothing more than a tax offset.

Payments to Selected Groups Under a UBI ($ billions)

Economic Illusions

The concept of a pure UBI without massive changes to the tax code or other spending cuts is nothing more than a fantasy. Yang, for example, proposes to finance a UBI with a 10 percent value-added tax as well as vaguely described increased taxes on “polluters and the wealthiest Americans.” Yang’s proposal is therefore nothing more than a shift in the tax burden from the poor and middle class to corporations and the wealthy. Changes in tax rates and deductions could accomplish an identical result. But through a sort of arithmetic shell game, Yang instead produces a revolutionary proposal.

AIER Research Fellow Michael Munger demonstrates how a more modest “basic income guarantee,” a means-tested version of a UBI, could similarly be implemented through straightforward adjustments to the tax code. In the end, this is the only form of federally driven aid to the poor that makes any sense.

As an immediate alternative to the expensive and complex bureaucratic nightmare of our current welfare system, cash payments with simple means tests should be a no-brainer for those supporting smaller government. But this approach needn’t be more than a stop-gap solution. In forthcoming articles, I will argue that the future lies in aid that is voluntary, decentralized, and locally focused.

Sign up here to be notified of new articles from Max Gulker and AIER.

Max Gulker is an economist and writer who joined AIER in 2015. His research often focuses on free markets and technology, including blockchain and cryptocurrencies, the sharing economy, and internet commerce. He is a frequent speaker at industry conferences, especially on blockchain technology. Max’s research and writing also touch on other economic topics, including governance, competition, and small businesses.

Max holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University and a BA in economics from the University of Michigan. Prior to AIER, Max spent time in the private sector, consulting with large technology and financial firms on antitrust and other litigation. Follow @maxgAIER.

This article was sourced from AIER.org