By Jason O’Day

By Jason O’Day

In 2018, the federal government paid $357.3 billion in interest on the nation’s fiscal operating debt—$61 billion more than the previous year. That is more than seven times what it spent on education and enough to build 27 aircraft carriers. The combined interest payments of the four years from 2015 through 2018 total $1.2 trillion. That figure exceeds each of the top three categories of federal spending in 2018 according to the Truth in Accounting (TIA) State Data Lab.

Those categories are Health and Human Services (HHS) at $1.1 trillion (primarily includes Medicare and Medicaid), Defense & Veterans Affairs at $1 trillion, and Social Security at $1 trillion. The interest payment is projected to more than double by 2025, reaching $725 billion annually.

Social Security is the only one of those categories that has risen every year over the past decade. Between 2008 and 2018, Social Security expenditures rose by $247.2 billion when adjusted for inflation. As demonstrated by the chart below, Social Security spending exceeded $1 trillion for the first time in 2018 and HHS spending for the first time in 2015. The Social Security Board of Trustees says the program is on track to become insolvent by 2035 when the “trust fund” will be completely depleted.

If or when that occurs, the Board will automatically impose a 20 percent cut in benefits to all program recipients. The government’s projected insolvency with Medicare is less than seven years away, in 2026. Analysts say that Medicare will be much tougher to stabilize financially than Social Security because health care costs fluctuate sporadically as new medicines and procedures enter the market.

Questionable Accounting

These programs are even more unstable than they sound, in part because they do not meet the Treasury Department’s own definition of a trust fund:

In the federal budget, the term “trust fund” means only that the law requires a particular fund be accounted for separately, used only for a specified purpose, and designated as a trust fund.

Although worth keeping an eye on, the government’s projected insolvency of entitlement programs is an insufficient yardstick because the politicians and bureaucrats who oversee them do not adhere to the most basic standards of accounting.

According to the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board,

Until benefits become due and payable, there is no binding commitment over which a worker has control and so no liability can be recognized.

That probably sounds like Latin to most people, but it means that the government does not acknowledge its obligations to pay Social Security benefits beyond the checks it has to write for the current month. It is unethical to seize the fruits of a person’s labor without first obtaining their consent, even if indirectly. Every law-abiding citizen has the opportunity to push back against unfair taxes at the ballot box, yet the federal government is operating on money borrowed from Americans who haven’t even been born yet.

The three aforementioned categories are the primary drivers of America’s $22 trillion fiscal operating debt. They comprise the bulk of the $4.5 trillion in total federal expenses for 2018. I use the terms “national debt” and “fiscal operating debt” interchangeably but prefer the latter because a precise measure of our nation’s debt should include the unfunded promises to entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security.

By that metric, the true national debt is $118 trillion, or $774,000 per taxpayer, as indicated by the debt clock, TIA’s website. The ratio of fiscal operating debt to GDP is currently 104 percent, the highest peace-time debt in American history. This is a daunting reality, but history offers a glimmer of hope.

Lessons From History

The debt to GDP ratio surged from 48 percent in 1942 to a peak in 1946 of 119 percent, spurred by World War II. The silver lining is that within 10 years, the ratio was nearly halved, dropping to 61 percent by 1956. That debt was much easier to reduce because the underlying federal spending increases behind FDR’s New Deal programs, World War II military expenditures, and the Marshall Plan were mostly temporary.

By contrast, spending for the entitlement programs that are driving our modern national debt shows no signs of slowing down.

The prospect of the United States growing its way out of the current national debt is dubious and wishful thinking.

As conservative radio host Mark Levin has frequently pointed out, the laws of economics are not unlike the laws of physics. Absent any serious entitlement reform, which is often deemed the third rail of American politics because of how controversial it is, the laws of economics will eventually crush political promises to Social Security and Medicare. At some point in the future, perhaps within the next half-century, interest on the national debt will eat up the federal budget to the degree that paying off any substantial portion of the debt will be unfeasible, and fighting a large-scale, multi-year war will become fiscally impossible.

Entitlement Reform

It would be illegal for me to take out a credit card every year using the names of random children and max out the spending limits. That’s essentially what federal politicians do to future generations by continuously passing omnibus budgets with massive deficits and pretending that Social Security can exist perpetually the way it is. Millions of disabled Americans rely on Social Security to survive. Millions of workers expect to eventually receive what they were forced to contribute and promised would be paid back in dividends to supplement their retirement. Fulfilling these promises will require a massive increase in the payroll tax.

Republicans have made a few noteworthy attempts at entitlement reform to avert such dire circumstances. The most significant was President Bush’s failed effort to reform Social Security by transitioning it toward a system of individual accounts for future beneficiaries instead of one large trust fund. In 2011, Paul Ryan floated a proposal that would have transformed Medicare into a voucher-like system. The Graham-Cassidy Bill of 2017 came the closest to passing but died in the Senate. It would have turned Medicaid into a system of block grants, limiting the funding each state could receive.

President Trump campaigned on a promise to refrain from making any cuts to Social Security or Medicare. Thus far he has kept that promise. Unfortunately, the trajectory of spending on those programs and the debt they incur pose a grave threat to the stability of the world in which our children and grandchildren will live.

Jason O’Day is a communications intern at Truth in Accounting, a nonprofit organization based in Chicago that researches government financial data.

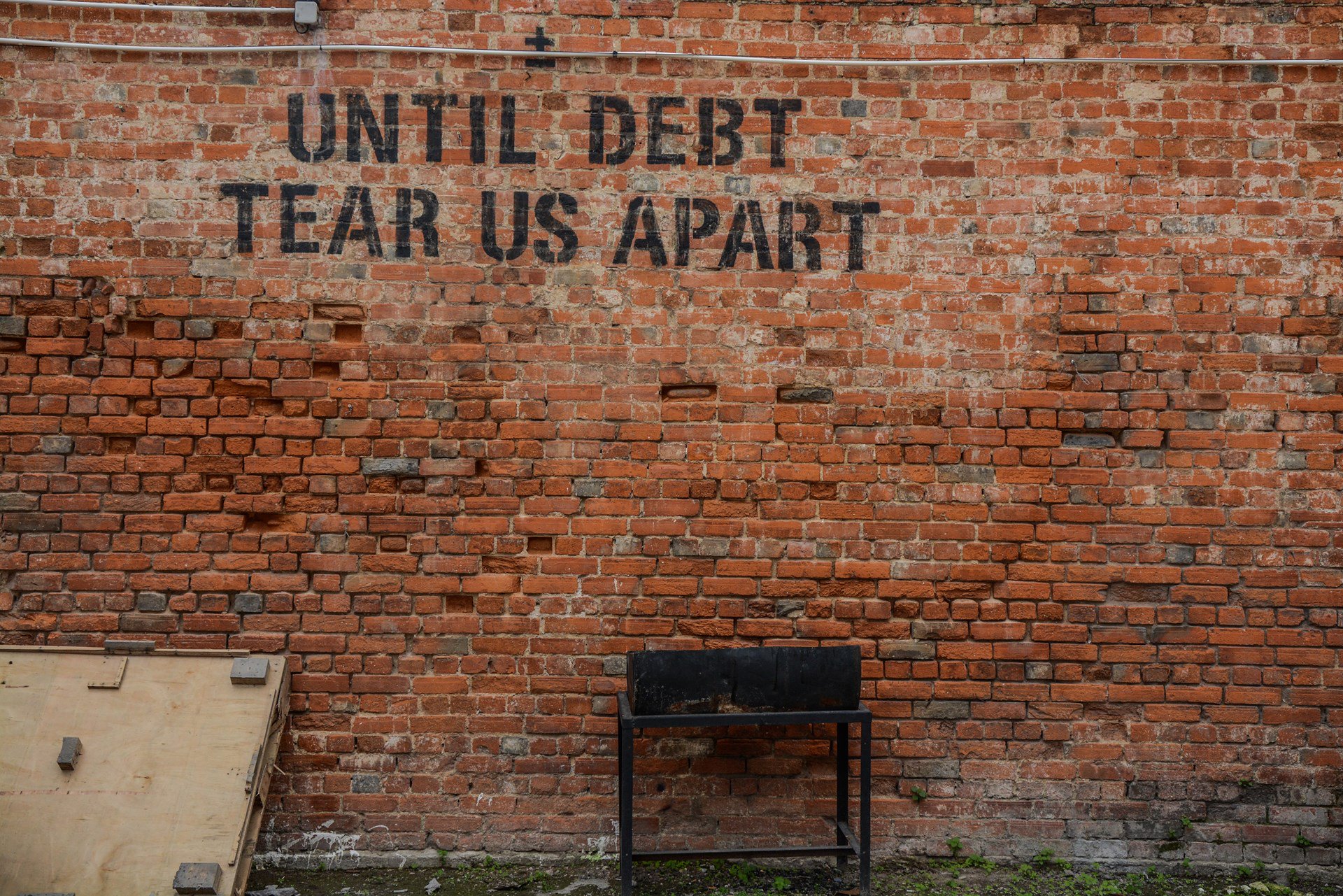

Photo by Alice Pasqual on Unsplash

This article was sourced from FEE.org