Twenty-five years ago, the most successful 20th-century experiment in liberty — begun inadvertently, as always — came to an end. In April 1994, demolition of the taxless, unregulated, autonomous capitalist enclave known as the Walled City of Kowloon was completed, ending nine decades of an unparalleled experiment in utter statelessness.

Similar to the Moresnet condominium, the Walled City emerged out of a political stalemate: a Chinese military outpost abandoned in British-administered Hong Kong. And into that 0.03 km² limbo poured tens of thousands of individuals, seeking shelter within the labyrinthine passageways and tunnels of the old fortress. The population grew relentlessly over the years to number between an estimated 30,000 and 50,000 residents — a bustling hive of hardscrabble entrepreneurs, political refugees, do-gooders, gangsters, artists, and, most of all, workaday individuals and families.

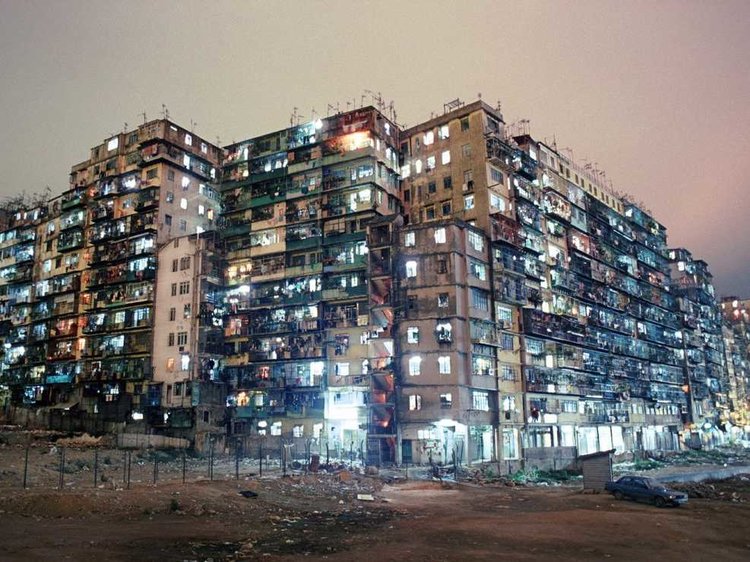

Physically, it was a bizarre setting for an exposition of anarcho-capitalism — a slapdash city more closely resembling a Borg cube than the hidden valleys, alpine vistas, or artificial islands that libertarian and anarchistic imagery often envisions. As haphazard as it appeared, though, it was sturdy both structurally and functionally. By one account, the great economic miracle of Hong Kong throughout the 1980s — from booming restaurants to machine tooling, textile manufacturing, toy making, and beyond — was expedited in no small part by the hundreds of hugely productive, if claustrophobic, workshops (many doubling as the owners’ homes) operating around the clock within the Walled City. Unlike their counterparts in Hong Kong proper, firms inside the Walled City were free of licensure restrictions and fees, their owners able to exercise personal discretion as to workplace conditions, operating schedules, and so on; thus they were eagerly subcontracted to by businesses outside the Walled City to exploit cost savings, loopholes, and arbitrages.

A minor thread of revisionist disparagement has endured since the Walled City’s destruction — namely, that the Hong Kong police raids throughout the ’60s and ’70s were indicative of rampant crime within the old fortress. In fact, the police actions were an expression of frustration regarding the failure of drug prohibition in the rest of Hong Kong. Within the Walled City, in fact, opium dens ran quietly alongside a world-famous rehabilitation clinic, and the latter operated freely: not precisely with the blessing of, but without any interference from, the narcotic dealerships. Both drugs and rehabilitation from their use were readily available; predictably, both were sought after. The myth fails to withstand even superficial scrutiny: if violent crime was ubiquitous within the Walled City, why was there interminable interest among individuals and families to move into even the tiniest of living spaces? How did mail carriers deliver parcels for decades without incident? And why did groups of wealthy Hong Kong revelers seeking a night on the town regularly patronize the gambling parlors and exotic eateries within its twisting confines?

Facts about the Walled City of Kowloon stand in defiance of the perennial detractors of statelessness: not only were crime rates low despite the absence of a standing police force, but proven, typhoon-withstanding construction was accomplished without building codes. The common defense was upheld and maintained without military units. The Walled City of Kowloon did not evince any flags, anthems, or pledges, but nevertheless developed as tight a sense of community as one can imagine. Indeed, the idea that mayhem is consort to statism rather than anarchy is unambiguously championed in the historical record of efficient disorder within the Walled City.

Beginning in 1987, 10 years before the scheduled turnover of Hong Kong to China, the disposition of the Walled City figured high on the list of issues requiring resolution. Unsurprisingly, the decision was made to level the territory. The “anti-demolition squad” — a rough equivalent of a volunteer “militia” or “national guard” — successfully hindered and delayed efforts to demolish the Walled City for several years. But by 1992 reparations were being offered, and the following year the dismantling began, sending an estimated 900 businesses and 10,700 households back within the grasp of government authority.

“This is a good place to raise a family,” said one woman, as the evictions progressed. “We will never find a place like this one again.”

The history of the Walled City teems with symbolism: a libertine enclave caught both spatially and temporally between old colonialism and Communism, ultimately outliving both; a commercial refuge which, in its unhindered functioning, buried cannons and ramparts; a productive if chaotic urban tract replaced by a monument to planning’s idleness and waste; a public park. Above all, it should be lost on no one that for decades, the most densely populated place on earth happened, not coincidentally, to be the place with the least government — a “harmonious anarchy,” as described by the New York Times.

All seekers of liberty are forced, at some point, to reflect soberly upon our chosen path: are we ever to turn our faces toward the sun standing on truly free soil? Will we, even if fleetingly, know a world, independency, micronation, or tribe animated by private contract, nonaggression, and voluntaryism? Perhaps not. But remembering the Walled City of Kowloon — a green shoot of freedom standing for nearly a century in contrast to the gray, gnarled landscape of statism — should energize our peaceful fight.

Sign up here to be notified of new articles from Peter C. Earle and AIER.

Peter C. Earle is an economist and writer who joined AIER in 2018 and prior to that spent over 20 years as a trader and analyst in global financial markets on Wall Street. His research focuses on financial markets, monetary issues, and economic history. He has been quoted in the Wall Street Journal, Reuters, NPR, and in numerous other publications. Pete holds an MA in Applied Economics from American University, an MBA (Finance), and a BS in Engineering from the United States Military Academy at West Point. Follow him on Twitter.

This article was sourced from AIER.org

By

By