States across America are increasing the minimum wage. This is bad policy for numerous reasons, but the movement nonetheless appears to be gaining steam.

Eighteen states began 2019 with new minimum wage laws. Several more passed legislation in 2019, including Maryland, where legislators overrode a veto to pass a $15 minimum wage. McDonald’s, perhaps reading the landscape, recently announced it will no longer lobby against mandated increases in workers’ pay.

The reasons for this aren’t hard to divine. Minimum wage increases are lousy policy—violating the rights of employers and workers while denying the most vulnerable in society the dignity of work—but they are great politics.

Why? Because minimum wage laws are popular. Polls show more than half of Americans support raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. Popularity, however, is a poor metric for sound policy. Roughly the same percentage of Americans, for example, say torture is permissible.

What’s the Big Deal?

It’s easy to think minimum wage hikes are not a big deal, partly because we’ve had them for so long. The first federal minimum wage, which mandated $0.25 per hour, was enacted in 1938. It’s safe to say that no one today can remember working at a time when a minimum wage didn’t exist. The sky has yet to fall these last 80 years, minimum wage supporters can point out.

And then there’s the fact that today economists disagree on the extent to which minimum wage laws reduce employment. Though few economists are willing to say sharp minimum wage increases won’t result in substantial job losses, some do. They often point to the Card-Krueger study, which found that a minimum wage hike in New Jersey did not increase unemployment in the state’s fast food sector, to suggest that perhaps minimum wage laws are not as harmful as once thought.

It’s important to remember, however, that not all minimum wage laws are equal. A state that increases the hourly minimum wage from, say, $4.25 to $5.05 is not doing workers or businesses favors, but most economists would agree that it’s doing less harm than the legislature that increases it to $25 an hour. (As it happens, the Card-Krueger study analyzed the effects of a minimum wage increase from $4.25 to $5.05 and examined data over a short window of time, just 11 months.)

Minimum Wage Hikes in Venezuela and Greece

What many people have overlooked is that it is precisely this kind of tinkering in labor markets that preceded—and, to one degree or another, no doubt precipitated—two of the most notable economic meltdowns in a generation.

In Greece, the national monthly minimum wage increased from less than 600 euros in 2000 to nearly 900 euros in 2011. That 50 percent hike was far higher than Greece’s neighbors.

Panos Mourdoukoutas, an economist who teaches at Columbia University, has pointed out what followed.

That was a booming period for the Greek economy, financed by debt, plenty of debt. And we all know what happened when the debt came due, and the Greek economy slid into its worst postwar depression.

And then there is Venezuela. Historian Rainer Zitelmann, the author of The Power of Capitalism, has noted that Venezuela’s road to perdition began when the government, ahem, reformers created what was possibly the most heavily regulated labor market on the planet.

“Venezuela’s reversal of economic fortune started in the 1970s, long before Hugo Chavéz came to power, making conditions even worse,” writes Zitelmann. He continues,

One of the reasons for Venezuela’s problems was the unusually high degree of government regulation of the labor market. From 1974 onward, the applicable rules were tightened even further to a level that was unprecedented almost anywhere else in the world–let alone Latin America.

Just how far did the Venezuelan government regulate its labor markets?

From adding the equivalent of 5.35 months’ wages to the cost of employing someone in 1972, non-wage labor costs soared to add the equivalent of 8.98 months’ wages in 1992.

There are additional lessons here. How did Greece respond to its economic crisis? The country, which saw its unemployment rate increase from 7 percent in 2008 to 28 percent in 2013, slashed its minimum wage from 876 euros to 683 euros.

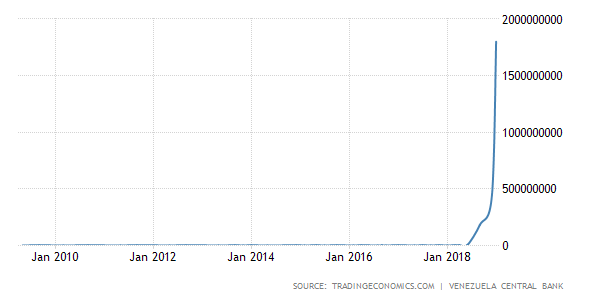

Greek lawmakers would have been wiser to repeal the minimum wage altogether. Yet their response was infinitely better than Nicolás Maduro’s, who in January announced a 300 percent increase in Venezuela’s minimum wage. This action was taken on the heels of six minimum wage increases in 2018. Behold:

source: tradingeconomics.com

Many, of course, will laugh or scorn such a response in the face of economic catastrophe. But Maduro is simply applying the same logic as US politicians who insist that wages should be determined by what a politician dictates rather than by productivity.

Where Will It Stop?

I’m not implying that economic catastrophes of Greece and Venezuela were caused solely by minimum wage laws or labor regulations, though they surely helped bring each about. Rather, these policies were part of a gradual shift that saw more and more market decisions replaced by central planning.

In The Law, Frédéric Bastiat warned about the inevitable consequence of using the coercive power of government in ways other than that for which it was intended (the free exercise of rights).

What Bastiat understood is that once lawmakers begin to use the law to build utopia instead of protecting liberty, they will find it difficult to cease. When markets are distorted and hunger or pain strike, politicians will be tempted not to use the law less, but more. This is why it was natural for Maduro to use the very same mechanisms (regulatory power and coercion) to resolve a crisis that these mechanisms precipitated.

Many US states passing minimum wage laws may very well, like Greece, enjoy a season or two of summer. Economics, after all, is tectonic. The shifting of plates in the earth beneath our feet may be invisible to us, but it’s happening. So, too, in economics, where unseen consequences ripple from every policy that supplants consumer choice with government fiat.

How many more people are arrested after being priced out of a labor market? How many entrepreneurs decide they can’t afford to start a business or expand an existing one? Economists are skilled at counting jobs lost, but what about those never created in the first place?

We’ll never know. But there is one thing we do know: Eventually, as it inevitably does, crisis strikes. The question Bastiat would ask, then, is where will the law stop?

Jonathan Miltimore is the Managing Editor of FEE.org. His writing/reporting has appeared in TIME magazine, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, Forbes, Fox News, and the Washington Times.

Reach him at [email protected].

This article first appeared at FEE.org

By

By