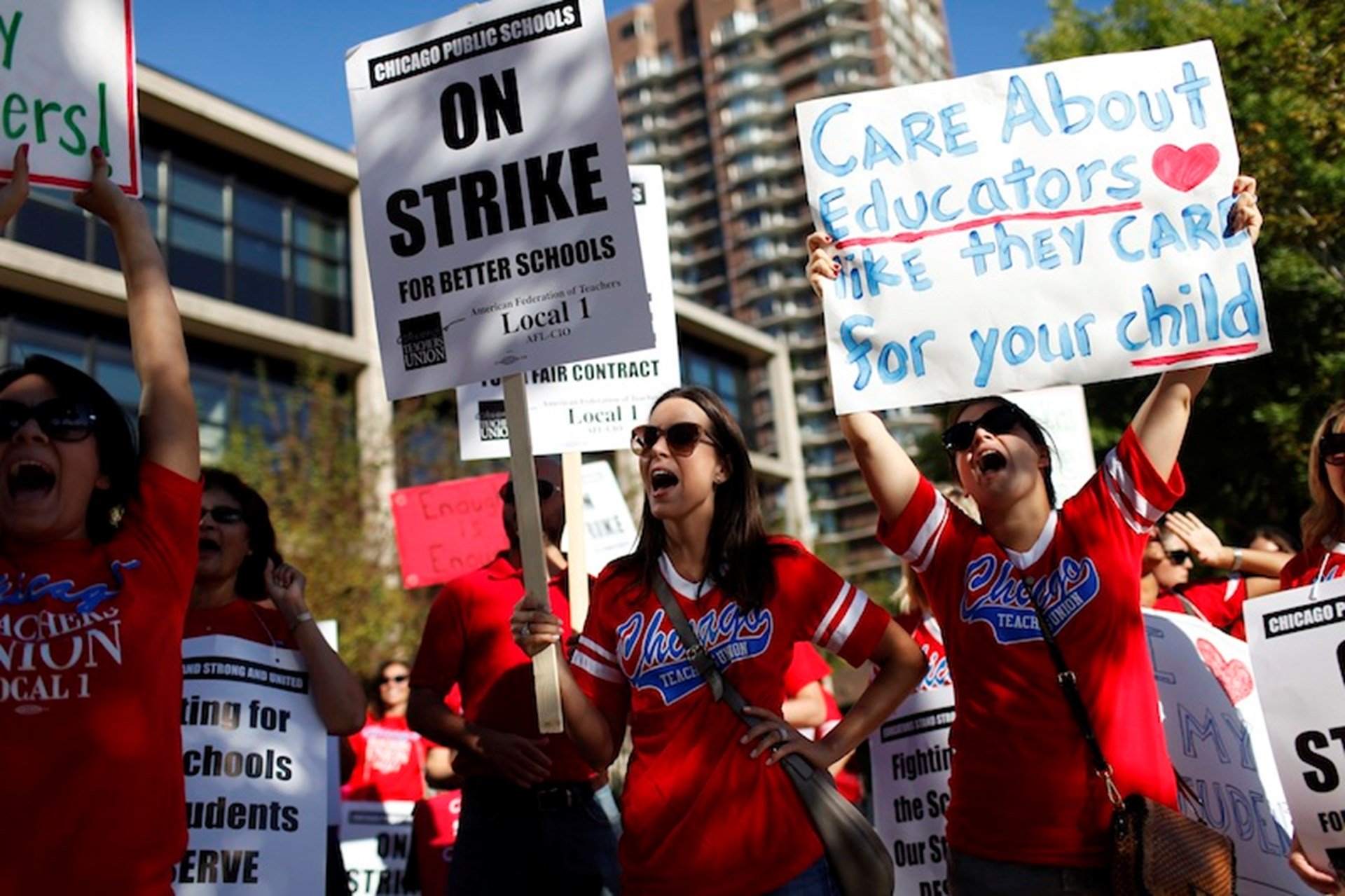

As the Chicago teachers’ strike continues with no end in sight, 300,000 students spend another day outside of the public school classroom. Chicago’s mayor, Lori Lightfoot, says this is damaging to children.

“We need to get our kids back in school,” the mayor said Thursday, CNN reports. “Every day we are out, that hurts our children.”

But Are the Children Really Hurting?

As the Chicago strike shows, when government schooling is not the centerpiece of a child’s life, community organizations step up to provide support and care. Museums, churches, libraries, and a multitude of civic non-profits are opening their doors to children displaced by the teachers’ strike, and public parks and playgrounds abound.

Some of the organizations that are offering a safe place for children to gather include the YMCA and its 11 locations across Chicago. As CNN reports: “Depending on the location, these programs may include classes, swimming, math lessons, arts and crafts, and sports.”

The Boys & Girls Club of Chicago, as well as a similar but separate organization, the Neighborhood Boys & Girls Club, are open all day for children affected by the strike. Many arts organizations throughout Chicago are offering special programming for students in a range of topics, from theatre to dance to visual art.

The city’s aquarium is offering immersive exploration opportunities for the children, along with an after-school care option. Other science organizations are doing the same. Sports camps are sprouting through local athletic and recreational organizations, and area gyms are opening up and offering adult supervision.

Churches and religious organizations, including the Jewish Council for Youth Services and The Salvation Army, are providing care, activities, and in some cases meals. For the estimated 75 percent of Chicago children who usually receive their meals through the school cafeteria as part of the federal school lunch program, they can still go to their local school building, staffed by non-unionized administrators, and receive their eligible breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals.

Finally, there are the Chicago libraries, which are scattered across the city and open to everyone. Libraries are models of true public education, inviting all members of a community, regardless of age or background, to learn without the coercion characteristic of compulsory mass schooling.

Library patrons can take advantage of optional classes and lessons, ask for help when needed, or pursue their own curiosities using the library’s abundant physical and digital resources. Libraries are incubators of community-based, self-directed public education. As Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in Between the World and Me, which claimed the 2015 National Book Award: “I was made for the library, not the classroom. The classroom was a jail of other people’s interests. The library was open, unending, free” (p. 48).

What a Vibrant Civil Society Could Look Like

For many children in Chicago public schools, the classroom is quite jail-like, with metal detectors and armed security officers on campus, and school performance measures that should make us cringe. According to Chalkbeat, “nearly half of Chicago schools failed to meet the state’s threshold for performance on its new accountability system,” as evaluated by the 2018 Illinois Report Card.

Teachers’ strikes often show, however inadvertently, why we don’t need public schools to provide education to the public. Without government involvement and compulsion, civil society steps up and quickly mobilizes to care for children and families.

We see just a small glimpse of this in the brief time that the Chicago students have been displaced due to the teachers’ strike, but imagine how much more would emerge if the shadow of compulsory public schooling didn’t loom so large. Neighborhood organizations and businesses, churches and non-profits, non-coercive public spaces like parks and libraries, and families, would be empowered to support and educate the children around them.

Indeed, this is how education worked prior to the mid-nineteenth century passage of compulsory schooling laws that narrowed a broad definition of education into the singular concept of forced schooling.

Children don’t need government schools to educate them. Instead, they need a vibrant civil society that buttresses families and inspires communities to come together and educate their own children in a variety of ways using a variety of resources. The teachers’ strike impact only gives a glimmer of what a vibrant civil society could look like if it were consistently charged with caring for and educating children.

Far from hurting children, the Chicago teachers’ strike shows us the way to truly help them.

Kerry McDonald is a Senior Education Fellow at FEE and author of Unschooled: Raising Curious, Well-Educated Children Outside the Conventional Classroom (Chicago Review Press, 2019). She is also an adjunct scholar at The Cato Institute and a regular Forbes contributor. Kerry has a B.A. in economics from Bowdoin College and an M.Ed. in education policy from Harvard University. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with her husband and four children. You can sign up for her weekly newsletter on parenting and education here.

Image credit: TMT-photos on Flickr | Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0 — https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

This article was sourced from FEE.org

By

By