By Vin Armani

By Vin Armani

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

The ignorant view on Bitcoin, at least since the Silk Road takedown, has been that “Bitcoin is used for crime.” The media’s scandalizing of the Silk Road story certainly introduced the meme that Bitcoin is used for purchasing drugs. There have also been breathless pieces in major newspapers in recent years about Bitcoin being used to fund terrorism. There is no doubt that Bitcoin is used for these purposes, but compared to the use of paper fiat (particularly US Dollars) in illicit activities, Bitcoin is barely a drop in the bucket.

I have developed significant patience for dispelling myths about “Bitcoin as a currency of crime” when in conversations with nocoiners (those who have never participated in the cryptocurrency world), but I was quite shocked recently to hear individuals who called themselves Bitcoiners being quite vocal about Bitcoin, and other cryptocurrencies, being used as a tool for money laundering. It gave me pause and got me thinking about whether Bitcoin could, in fact, be used as a vehicle for money laundering. It turns out that Proof Of Work cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin can indeed be used for money laundering, but not at all in the way that was being claimed.

In this article I will give a brief explanation about the purpose and mechanics of money laundering and explore how Bitcoin mining is potentially a quite interesting means of laundering money.

As with so much misinformation (disinformation?) as of late in the world of Bitcoin, this new Bitcoin money laundering meme has its roots in the mind of one Craig S. Wright, the man known to most as “Faketoshi.” In his talk at CoinGeek Toronto at the end of May, and in a follow-up blog post a few days later, Craig stated that privacy coins, such as Monero, and “coin mixing” protocols, like CoinJoin (BTC) and Cash Shuffle (BCH), “facilitate money laundering.” He warned, “On the day a case of money-laundering facilitation starts that is connected to Monero, all Monero globally stops trading.” His reasoning was that, “It doesn’t matter whether you’ve been a criminal before you start using such systems; the mere fact that you are aiding and abetting and allowing criminals to mix money with your funds makes you a part of the system.” But is mixing unspent transaction outputs or using a privacy coin to prevent tracing of your funds back to a previous transaction a form of money laundering? Not even close.

One of the most memorable scenes from the classic 1990 gangster film Goodfellas is the gang getting together at their hangout for a Christmas party. They have just successfully pulled off the Air France heist (based on the true Lufthansa heist by Henry Hill and Jimmy Burke). Jimmy, played by Robert Deniro, gave specific instructions to the crew not to make any large purchases, lest they raise suspicion and bring heat down on them. In two wonderful moments of comic relief, one crew member has bought a brand new pink Cadillac coupe for his wife and another has bought his wife a $20,000 white mink stole. Jimmy is flabbergasted. This scene illustrates the entire purpose of money laundering. There is no point in making money if you can’t spend it, but how can you spend significant amounts of money if you can’t explain from where you acquired the funds. An otherwise “unemployed” individual buying brand new cars and expensive clothes is going to raises suspicion and perhaps bring an investigation by law enforcement down on his head. He needs to find a way to take his “dirty” money, earned through illicit activities, and turn it into “clean” money, that appears to have come from legitimate activity with a benign “paper trail.” Thus, the term “money laundering.” As you can see, however, simply shuffling the history of your bitcoins on the blockchain (or using Monero) doesn’t solve the fundamental problem of accounting for how you acquired the cryptocurrency in the first place.

Netflix’s excellent drama, Ozark, gives a glimpse into the basic mechanics of the money laundering game. The series, greenlighted for a third season, follows a financial adviser (and money launderer) and his wife (played by Jason Bateman and Laura Linney) who find themselves in the Ozark region of Missouri attempting to clean the money of a Mexican drug cartel. The show has spectacular performances from the entire cast and clearly the writers did their homework on the world of money laundering. Bateman’s character immediately takes control of a strip club and a failing hotel (complete with bar and dock). These two businesses are mainstays of money laundering. In a nutshell, the money launderer’s racket is:

- Find a business that has significant cash receipts. Strip clubs and casinos are some of the best in this regard.

- Account for fictitious sales, particularly of items without inventory that must be replenished by purchasing supplies from vendors. Lap dances that never happened or empty hotel rooms accounted for as occupied fit the bill.

- Deposit the dirty cash into the reserves as the revenue from the fictitious sales.

- Pay taxes on the revenue and take the profit from the business as “clean” money.

Of course, one could conceivably do the above scheme with Bitcoin or Monero, but the simple fact that a business like a strip club or hotel would be taking in such a significant amount of cryptocurrency would be enough to raise red flags in and of itself. That the coins were anonymized would be of little help in the case of an investigation by law enforcement or tax authorities. As always, paper fiat is the king currency of crime.

Using Bitcoin as a money laundering vehicle is possible, but not in the way suggested by Craig Wright. Indeed, anonymizing of transactions is of no consequence when using Bitcoin to clean illicit revenue.

As far as I have been able to see, there are two methods for laundering money using Bitcoin or other Proof Of Work currencies. The first method is for turning dirty fiat into clean bitcoin. The second is for turning dirty bitcoin into clean bitcoin. Both can only be accomplished by a miner with significant hashpower on a network. The higher the percentage of a network a miner controls and the more liquidity the coin of that network has, the greater the amount of dirty money a miner can conceivably clean.

Bitcoin miners are rewarded for finding a block with what is called a “coinbase” output. While there are still block rewards and new coins are being issued, coinbase outputs include some newly minted bitcoins. That amount was initially 50 bitcoins, but we have gone through two “halvings” and now the amount received by the miner finding each new block is 12.5 bitcoins. In addition to the block reward, miners are rewarded with the miner fees from any transactions in the block. Generally, both of these values are added together and delivered in the first transaction of the block. That transaction has no previous input. This means that there is no “trail of transactions” that precedes the transaction. The coinbase funds are “clean Bitcoin.”

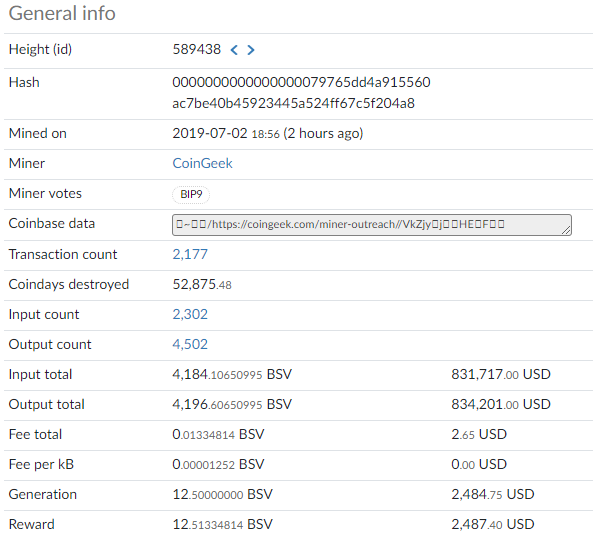

Below is a recent example, pulled from Blockchair, of a block mined by CoinGeek on the BSV network. BTC, BCH, and BSV are all basically identical in terms of how block rewards are delivered.

You can see that the block reward (“Generation”) is 12.5 BSV and the total fees are .01334814. The total reward of 12.51334814 BSV is delivered in the coinbase transaction for that block. For the would-be money launderer this mechanism is incredibly attractive. Let’s examine how a money launderer could leverage the block rewards and fees.

Bitcoin turns electricity into money. A miner’s primary ongoing expense is the electricity used to power his mining rigs and any necessary auxiliary equipment he needs to keep that equipment cooled. If the equipment gets too hot, the performance degrades. It is primarily the cost of electricity in a given region that determines whether or not a miner can be profitable on a given network. As the mining sector becomes more competitive, we see operations moving to countries and regions with the lowest electricity costs. At first glance, because electricity is metered (often by public, government-owned utilities), mining seems like a business where the paper trail is pretty solid. In fact, many illegal indoor marijuana grow operations have been busted due to their electrical bills being far too high, raising red flags. The Bitcoin miner looking to launder dirty fiat, however, has a trick up his sleeve… or, rather, in his basement.

Any data center worth its salt has backup power supplies. The largest and most professional data centers have industrial diesel generators (generally in the basement of the building) that can be turned on in the case of a power outage. These generators can be used to power the entire facility, giving nearly “100% uptime” even in the case of catastrophe. These generators are also notable because they are not grid-tied. That is, there is no way for anyone outside of the data center operator to know if the generators have been turned on or how much electricity they have generated. In theory, a data center could run indefinitely off of just its diesel generators, so long as adequate fuel levels could be maintained. This is not only true of diesel power plants. Technically, a natural gas or solar power plant could work as well. For the money launderer, however, diesel is an attractive fuel because of its ubiquity and the lack of scrutiny for cash purchases. A busy truck stop can take in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in diesel fuel revenue, in cash, every day. The scheme is actually quite simple.

- Power some percentage (perhaps 20%) of your data center with “mains” electricity delivered by the municipal system. Power the majority of your data center from diesel generators.

- Use dirty fiat to purchase diesel fuel.

- Use the diesel fuel to power the generators.

- Report your electricity costs as only the mains metered usage. Report all of the revenue from your mining operation.

In this scenario, the paper trail is clean, and so are the coinbase bitcoins recorded as revenue. Even if the fuel is purchased at the current retail price, I’ve calculated that a miner using such a scheme, if he had a large industrial generators, could generate electricity at around 13 cents per kilowatt hour. This is the world average cost.

One of the great advantages of using diesel fuel to run such an operation is that the fuel itself then becomes a form of currency. For example, a Mexican drug cartel could use their ill-gotten gains to purchase a large amount of fuel on a tanker. That tanker could then sail, unmolested and not suspected of anything nefarious, to whatever country the miner is in. The fuel can be unloaded by legitimate, licensed and bonded carriers. The fuel can then be delivered, in tanker trucks, to the data center. This activity wouldn’t so much as raise an eyebrow among the local authorities in the miner’s jurisdiction. The Bitcoin generated from this activity would have a clean provenance and could be moved or sold at will.

Eventually, after several more halvings, the miner reward for generating blocks will no longer be significant enough to participate in the above operation. Luckily for the money launderer, the fee reward can also be used as a vehicle for laundering of funds. The fees cannot necessarily be used to directly launder dirty fiat but it can be used to launder dirty bitcoins. Scenarios where such laundering would be necessary would be in the case of something like an exchange hack, or a malware ransom. Additionally, funds gained through darknet activities might also be excellent contenders for this type of laundering. The scheme for this activity is as follows.

- Use any illicit funds to create many chained transactions, each simply outputting to a new address and generating miner fees. The object is to slowly “bleed away” the total over many transactions until the total amount has been spent as fees (minus a final dust amount of under ~600 satoshis). Imagine this as something akin to a cheese grater, where the grated cheese are fees and the block is the illicit sum of Bitcoins.

- The miner generates these transactions himself and does not broadcast them to the network.

- When the miner finds a block, he includes these transactions in his own block, thus collecting the fees in an output with no transaction trail, a clean coinbase output.

- Report the revenue as simple mining revenue.

Miners can choose whether or not to include transactions in blocks. Miners can choose to mine empty blocks or they can choose to mine transactions no other miner has seen. This ability for a miner to choose what he does and does not broadcast to the network forms the basis of Ittay Eyal and Emin Gun Sirer’s controversial 2013 paper on Selfish Mining. In this case, the miner is able to have plausible deniability regarding the provenance of the fees because there is not, at the current time, any facility to know whether or not a transaction included in a block had been broadcast to the entire network. There is simply no requirement, under the consensus rules of Bitcoin, that a miner relay blocks or transactions. It is in the best interest of an honest miner to do such relaying, but it is not mandatory that he does so.

A miner seeking to do either of these forms of money laundering would be detectable based on certain criteria:

- The miner would be willing to mine a network at break-even or a loss. There is always some shrinkage expected in the money laundering process. Even mining at a loss, however, it is conceivable that the amount of clean money launderer has at the end of the process is still considerably more than with other, more traditional laundering methods.

- The miner would have a strong desire to obtain majority hash power on a network, even if the price of the coin of that network wasn’t high as compared to competing networks that use the same hashing algorithm. The more blocks the miner can mine, the more total funds he can clear.

- The miner would have a strong desire to be able to create huge blocks. This is particularly true in the case of the fee scheme. Miner fees are computed in Satoshis per byte, so the higher the block size cap, the more money can be cleaned per block.

I have no evidence that any miner is, as of this moment, participating in either of the money laundering schemes that I mentioned. It does, however, seem curious to me that the miners (mostly on the BSV network) who seem to be the most obsessed with the idea of Bitcoin money laundering are the only miners whose behavior closely mirrors the criteria set out above. It will be interesting to see if evidence comes out in the future that implicates miners in this sort of behavior. I think it likely is just a matter of time before such truths are revealed.

Vin Armani is the founder and CTO of CoinText, co-founder of Counter Markets, instructor for CodeFromGo beginner’s coding course, and the author of Self Ownership. Follow Vin on Twitter.