Massive government debt, sky-high unemployment, the economy frozen, idle workers receiving payments from the government. This might sound like COVID-19, but I am actually talking about post-World War I Germany.

If your high school history teacher skipped this story, here’s a bullet-point recap:

- Germany lost World War I in 1919.

- Great Britain and France punished Germany with huge fines.

- Germans resented the fines and defaulted on their payments.

- France got fed up and in 1923 invaded Germany’s coal-rich Ruhr valley to extract payments themselves.

- Germans offered nonviolent resistance.

- German coal miners refused to work for the French occupiers, and the German government printed even more money to pay the miners so they could feed themselves and their families.

Fast-forward to 2020. Massive government debt: check. Entire sectors of the economy frozen: check. Large portion of population unable to work: check. Government giving handouts: check. Calls for more handouts: check. Pick any western country and this would be a pretty accurate description of its current state.

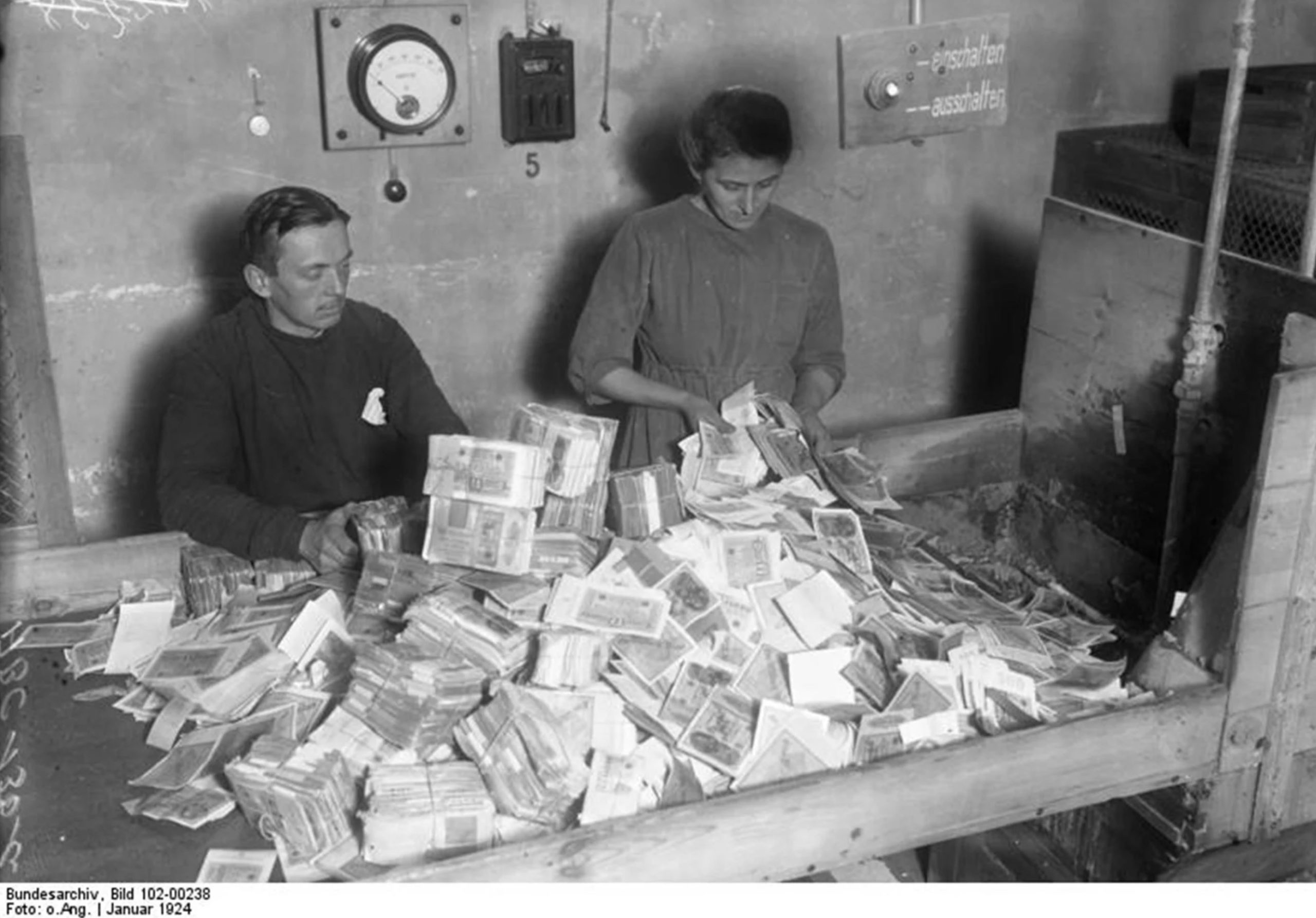

Let’s continue our history refresher. Remember those old black-and-white pictures of children playing with stacks of money? Or people burning money rather than firewood, because money was cheaper than firewood? That’s interwar Germany and as many assume, in the midst of a financial crisis caused by a Wall Street crash.

But these pictures are dated to 1923-1924 and the Wall Street crash didn’t happen until 1929. Why the hyperinflation then? As usual, it’s complicated. That hyperinflation was a product of many factors, especially monetary expansion, but printing money to pay workers who refused to work was one. It would be inaccurate to say that these payments were the sole cause of the hyperinflation (many would argue that inflation was already underway even before the French invasion). But, it would probably also be inaccurate to say this played no part in the hyperinflation.

Let’s go back to today. Giving people money “just because” is essentially Universal Basic Income (UBI). You can call it “stimulus checks” if you want, but if the one-time payments transformed into monthly payments, at some point you have to admit that the essential discussion is about UBI and not “extraordinary measures.”

There are many arguments for and against UBI, but one often overlooked issue is whether or not UBI stimulates the economy. The often-presented case follows a line of reasoning similar to this example: People receive their UBI, they spend that money on hot dogs, the owner of the hot dog stand will then have money to visit a barber, the barber will then have money to buy hot dogs. Call it the “Circle of Life” if you are into “Lion King,” or the “Circular Flow” if you are into economics.

But in order to “inject money” into the economy, you have to withdraw it from somewhere. Giving everyone $2,000 would “inject” $8 trillion into the economy, but if you increase taxes to raise that $8 trillion, you would withdraw money from the economy. You would be achieving redistribution, not stimulus.

Financing UBI by borrowing is another option. But borrowing is essentially using the resources of tomorrow to finance consumption today. You can consume more today at the expense of tomorrow, but that’s just saddling future taxpayers with debt.

There is an argument that borrowing should not be of concern because if we invest the borrowed resources right, it will lead to such an explosion of economic growth that repaying the debt will be easy; after all, businesses borrow all the time. But think for a second. How will borrowing money and giving it out to everyone, regardless of what they do, lead to long-term economic or technological breakthroughs?

Finally, there are those who say we should just print money and give it out to everyone. But there’s a cemetery of economies full of countries who’ve tried just that: Zimbabwe, Venezuela, interwar Germany, and even the Roman empire. Economic welfare is not how much money you have, but what you can buy with it. If you continue printing money, sooner or later money will lose value.

Admittedly, there are many factors involved that can mask inflation (e.g. falling oil prices). It could take much longer for the US to get there than interwar Germany, but the basic mechanism is the same.

Some say that inflation is a price worth paying to have everyone employed. But wouldn’t people receive UBI regardless of their employment? Unless someone has a logical explanation backed up with some empirics on how giving everyone money—regardless of whether you work or sit on a couch—encourages you to work, it is merely wishful thinking for now.

UBI is no miracle. Those that peddle it are no visionaries or Santas. Those who oppose it are not scrooges. It is a very serious issue with the potential to sever the link between effort and reward. If you worry about the situations where people ask to be fired because living on temporary benefits is better than working, what do you think will happen when we just start handing out money to everyone forever?

Source: FEE.org

Zilvinas Silenas became President of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) in May 2019. He served from 2011-2019 as the President of the Lithuanian Free Market Institute (LFMI), bringing the organization and its free-market policy reform message to the forefront of Lithuanian public discourse. In that role, he and the LFMI won two prestigious Templeton Freedom Awards (2014 and 2016) for Municipality Performance Index and the Economics in 31 Hours textbook, now used by 80% of Lithuanian high school students. Silenas holds degrees in economics from Wesleyan University and the ISM University of Management and Economics, and has served in numerous teaching and advisory roles. He and his wife Rosita live in Atlanta where they enjoy exploring the outdoors, attending social functions, and the occasional pickup basketball game.

Image credit: German federal archives on Wikimedia Commons | CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)

By

By